HOMENAJE A MAGDA FRANK

NELLY PERAZZO

Miembro de Número de la Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes.

I

French critic Nicolás Bourriaud points out, as one of the paths for artists today, “rooting (radicante)” art, a term that denotes a organisms whose roots grow as they progress.

He asks himself: “What if the scuplture of the 21st century were to invent itself with these works, whose project it is to erase their origin in order to promote multiply simultaneous or successive rootings?”. And later on, he states that artists have become the prototype contemporary traveller, “homo viator” whose passage by signals and forms remits to a contem porary experience of mobility, of displacement, of crossing.

Magda Frank does not belong to the 21st century, her art is deeply rooted in the 20th century and, because of being an errant figure herself, she does not highlight the themes of precariousness and erring to which Bourriaud alludes. Much the opposite, she clings, one could nearly say desperately, to the affirmative, the monumental, the search for similar concerns across time, a supporting base, which rescues her from this very “rooting” condition, to which she was dragged by one of the worst tragedies of the 20th century.

Born in Transylvania, graduated in Budapest, the horrors of war basically took her to France and Argentina, not going without her study grant in New York, her exhibitions in Tel Aviv, Yugoslavia (modern day Croatia) and São Paulo, as well as countless works in France, in Ajaccio (Corsica), among others mentioned by professor Magaz, in particular. Because Magda Frank does no draw for others to make large, she does all the work herself from beginning to end.

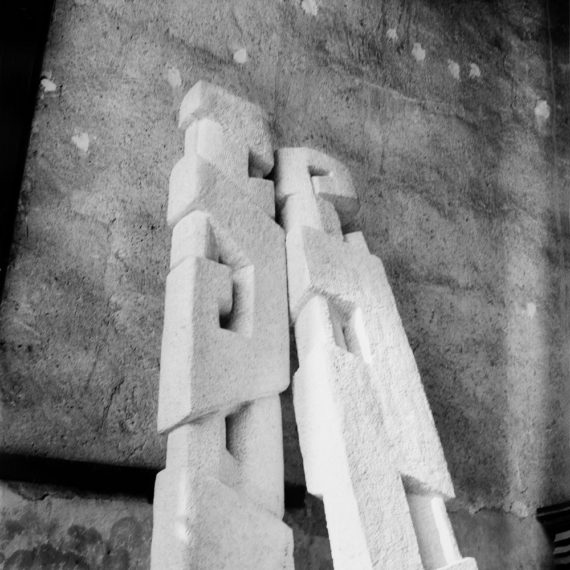

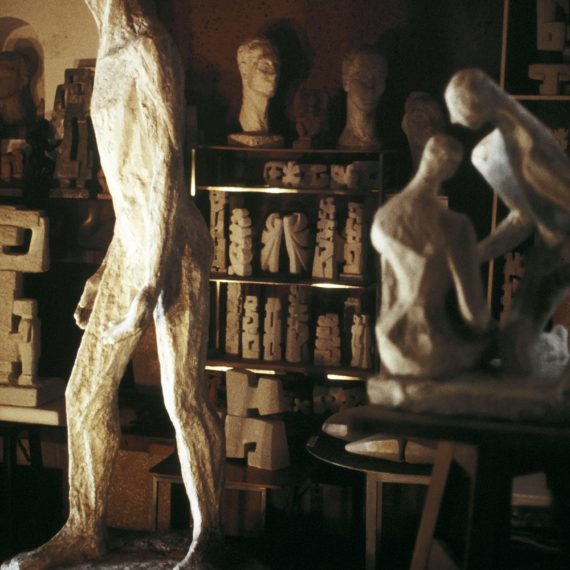

As written by Marc Gaillard, she is perceived in constant battle against the elements, stone, for example, with which she spars for a long time until she masters it, until she loves it, however only after a victory for which she had to pay the price of huge physical effort and the constant wielding of will and imagination. Magda Frank claims, in her work as sculptor, the capacity to give birth to a single, unique item at a time, which no machine or craftsman will be able to make, no matter how skilled.

Until the end of the task, there is something noble in this sculptor’s work crafting stone, a type of physical dialog with matter, a dialog that leaves behind marks, marks of hands, at times light and at others awkward or tierd by the weight of the hammer or the tip of the chisel.

Because Magda Frank ’s

life drains away at each work.

They are her reason for being, for surviving

She needs to focus this emotional load on something that, given the very fleeting nature of times and spaces, will not escape through her hands so quickly, that she may touch it, feel it, materialize it, incorporating this fully in her works.

My house and my workshop are inhabited by sculptures that are the companions of my life. I look to my own end with my head held high, because in my works, I have put the best there was in me. (1964 )

In the beginning, she did figurative sculpting. In The Big Man, the bearer of a tragic fate finds his apex in the first half of the 1950s. From then on, advice from her master Gimond at the Academie Jullien de Paris prevails: geometric construction is the skeleton of a sculpture. It is through this idea that she connects with the pre-Colombian and other forms of primitive art.

So, starting in 1957 she stops working in clay to sculpt wood, stone and marble

Her problem no longer is geometrize the human figure and becomes building the shape of her connection to the void, both inner and external, in her links, in her origins and in her own emptiness.

French critic Jean Jacques Levêque signals that Magda Frank’s sculpture is at the threshold where we pass from a sculpture of representation to another whose purpose lies in the shape and in the research of this shape, inaugurating a sculpture that is of entrance, rhythm. He also signals that she had started under the influence of Maillol, through her teacher in Budapest.

In reality, from the outset, she is numbered among the sculptors who strive for affirmative volumes, filled with simplified surfaces, decided profiles – which are the ones that brought splendor to the beginning of the 20th century like Maillol, Bourdelle, Minne.

However, she also merges Brancusi’s overwhelming influence, the undeniable father of the 20th century’s aesthetic essentialism – according to Renato Barilli – in her proposal to leave aside external intervention on natural data in order to accomplish a construction criteria ruled by its own laws. And therein is also present Henry Moore’s monumental grandeur. Magda Frank had no affinity with other artists; like her, immigrants from the East, such as Antoine Pevsner and Gabo who joined in the use of new materials, belonging to the new technological era; and chose the grand plasticity of solid blocks, the seduction of virtual volumes.

In dealing with displacements, the 20th century has countless rooting artists, as Bourriaud calls them: Magda Frank, Gabo, Pevsner, Kandinsky, Albers, Larionov, Gontcharova, Moholy Nagy, among so many others, however, the attitude is totally different. In this case, these were artists who were looking for a place with more freedom to work, but that were travelling for personal reasons, they carried their world along with them.

Magda Frank writes...like an errant without family, without country, without religion who will not leave us from her life naught but a few inert sculptures. That will not weep her loss.

The errant nature of today’s artists is totally different, it is a voluntary option, a way of life. They make of their errant ways, the theme for their work. Their search is based on their displacement. With totally different characteristics we might mention in Argentina, Teresa Pereda, and abroad, Rirkrit Tiravanija or Thomas Hirschorn, both mentioned by Bourriaud.

There are two fundamental aspects that must be taken into account in Magda Frank’s sculpture. The first is her relation with the primitive, to which more intense reference is made by professor Corcuera and the second, is her monumentality.

Many sculptors have turned their eyes to primitive art. Modigliani’s heads, the Portal of the Kiss, or Brancusi’s infinite column, the Works of Zadkine, Archipenko, Paolozzi, Marino Marini, Moore, Giacometti, among so many others, are located in a broad spectrum of different registers, in which attention and/or reflection on primitive art were fundamental.

In Magda Frank we have a point of intersection between the dive into primitivism and monumentality. The idea of monumentality is linked to the fact of celebrating, the relationship with society that attributes to her a symbolic content. For the primitive, monumental is the possibility of targeting their desire for permanence, for survival.

Magda Frank is the woman who writes.

…how many times have I pleaded TO death

To set me free of this life without hope.

And then I wanted to live. I want to live. (23-03-1959)

Sculpture has given her this possibility of support in a world that had been very hostile to her. For her, living was to become working, sculpting desperately, making no concessions, blow by blow.

Morning comes, I jump out of bed and hurry

Because my stone waits for me. My thoughts,

My feelings are for her.

I live for her and in her. (1976)

Faced with cruelty, death, loneliness, she clings to hers: I am a sculptress.

II

Between her individual exhibition at Maison Internacionale de la Cité Universitaire de París in 1955 and her long time permanence in that city in the 1960s, Magda Frank participated actively in Buenos Aires in a number of exhibitions that made clear the importance she had taken on in non-figuration in Argentina.

The Asociación Arte Nuevo, which held periodic meetings in its salons for painters and sculptors of this orientation, as well as modern architects and photographers, convened in December 1957, its 3rd Salon, and Magda Frank was among the participants. In the previous year, she had been appointed professor of the Fine Arts School and had been recognized at the Salão Rosário, province of Santa Fé.

Among other participations, we would highlight the distinction of having been invited in 1959, to take part in the Palanza Prize convened by the National Academy of Fine Arts of Argentina and her participation in the First National ANFA Salon (Non-Figurative Art Group).

III

It is interesting to detain oneself on other aspects of Magda Frank’s work: her flat sculptures on polychromatic wood and her drawings.

The first are connected to her being in contact with primitive art, in particular primitive American. They are as if they were stylized renditions in which she gives free reins to contradicting tensions. On the one hand, they display stability of composition in terms of the drawing per and are strongly bases in symmetry, on the other, they introduce subtle variants between the two parts joined along a central axis: whether by shape exchanges, edges outlined in a different color, or different friezes. The specular nature is never very strict. These drawings comprise the Angels and Archangels series.

Professor of Aesthetics of the University of Madrid, José Jiménez wrote

about the artistic image of the angel in the contemporary world.2

I made reference to the theme3 tracking the presence of angels in Blake, Gauguin, Klee and in the Argentinian Norah Borges, Marcelo Bonevardi, Eduardo Medici, Oscar Curtino, Giancarlo Puppo.

Magda Frank’s angles and archangels enter the long list started in the

country with the original musketeer angles of the Northwest of Argentina in the 17th century, sometimes solid and rigid as in polychromatic wood, at times ethereal and full of grace as in her stone sculptures. Jiménez wonders: why the need for so many angels?

There is no doubt that this is an image that spans some very different cultural elements. The angles of today’s artist do not illustrate a religious idea, they belong to a purely personal imaginarium.

Polychrome woods of the Archangels series

IV

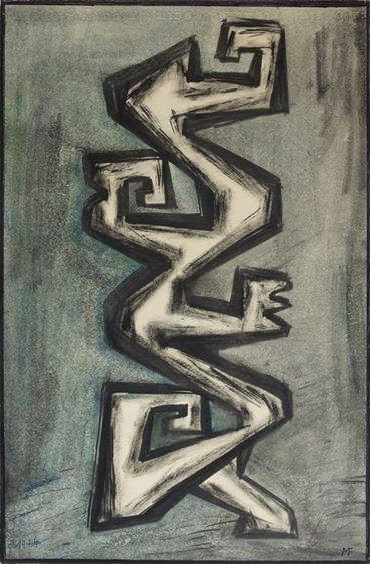

Another aspect of Magda Frank’s work that we are interested in highlighting is the extraordinary wealth of her drawings.

In her last operational phase, they were her refuge as paper cutouts were Matisse´s. For their rigidity, similar to primitive landscapes, they could be related to her research in the field of sculptures.

There are drawings of several different types. Some work in faces and bodies that could be considered to be workshop material; since they are not dated, except for a very few from 1955, this is hard to establish.

Some are clearings drawings of a sculptor for their suggestion of volume, other approach work on and over a plane.

The majority is in black and white, but there are some magnificentlycolored ones.

As techniques, we can detect, with a good margin of accuracy, paint, watercolors, graphite, crayons, softening stump.

__________________________

2 Jiménez José, El ángel caído. La imagen artística del ángel en el mundo contemporáneo. Ed.

Anagrama, Barcelona, 1982.

3 Perazzo Nelly, Encuentros con el ángel, En EOS Revista Argentina de Arte y Psicoanálisis, nº 3. Ed.

Fundación Banco Crédito Argentino, Buenos Aires, 1994.

Similar to what she does with her sculpture, at times she uses more than one texture in the same work. The variety of her resources when drawing draws our attention. At times she leaves outlines on a white backdrop, at times she maintains differentiation between backdrop and figure, in others she totally invades the surface of the base plane without any differentiation (all over).

There are some drawings connected with architecture with vertiginous effects of perspective created by the diagonals.

In general, Magda Frank moves very freely in her drawings. There is no doubt that they are interesting on their own, regardless of her excellence as sculptor.

Some of these, regrettably not closed, with her nervous trace or drawn out across distinctive points on the surface allude to the tragic nature of her own experiences.

I do not like to talk about my life and doubtlessly manifest it in a nearly subconscious way, in my work. The thousands of sketches kept in the drawers of my atelier are daily notes of my thoughts, feelings (…) For those who know how to read them, my drawings tell much more about me that I could do myself with words.

V

It is also necessary to mention some documents found that reveal how deeply she studied the art of sculpture in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Persia, Greece, Muslim art, Roman art, the end of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, the art of the late 15th century in France, the monumental art of the 16th century in France, Oriental art. She drew and marked out details of the properties of specific works. She drew every stained glass window in the cathedrals of Moissac, Chartres, among others, the floor plan of the cathedrals of Toledo and Bourges, Toulouse, side views, the arches.

Among her notes there is also pre-Colombian american art. These de tailed texts, some stemming from some of her own experiences, others from information obtained from books, shown the sound nature of her formation and her total delivery to the activity she had chosen to dedi cate herself to.

Many times, on learning about this artist’s life, I was reminded of the extraordinary Hungarian writer Sandor Marai, who, and above all in his autobiographic romance “Land, land”, refers to the suffering of his peo ple. Written in exile, he deploys it as a direct testimony of the suffering of Hungarian culture.

Marai writes: “I had to abandon Hungary, without conditions, without negotiations, without hope of returning, it was the moment to leave forever”.

These could have been Magda Frank’s words. On her return to her country important critics referred to her work in separate articles (4).

On the other hand, in Argentina, on Magda Frank’s arrival, the Hungarian colony was numerous and many of her fellow citizens had come for the same reasons.

This was the case of the extraordinary drawing artist Lajos Szalay who illustrated a book on the drama of Hungary edited by Delamerikal Magyarsag, the Hungarian daily newspaper of Buenos Aires

In her notes, Magda Frank wrote on January 21st, 1959 in Buenos Aires:

A sign of friendship … today I’d need one more than ever. I carry a wounded heart. Where to seek strength to raise myself above so much infamy? The sky is dark and large drops fall, when the call of a bird breaks the monotony of rain. A voice of hope. Soon the sun will appear again.