MAGDA FRANK AND THE SEARCH FOR A DAWN

Dra. Ruth Corcuera

Directora del Departamento de Antropología Cultural C.I.A.F.I.C. Miembro de número de la Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes.

Miembro de Número de la Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes.

The works of this unique artiste cannot but evoke in us the figure of de Jorge Luís Borges. Universes of books, libraries and museums. Looking for an ideal world, perhaps hidden in forgotten sagas or archaic cultures, in the idea of rebirth fed the dawn. In Las ruinas circulares, in refering to his character, Borges wrote that the purpose that guided him was not impossible, in spite of supernatural: “I wanted to dream a man; I wanted to dream him with detailed integrity and impose it on reality”.

Archaic art

We know that in creation not only what artists see is decisive, but also the way and attitude in which it is seen: the look that omits or adds. We know that those that face their work achieve their reality.

Magda Frank discovers archaic art in lectures and in museums, first in Paris and then in Buenos Aires. The information we have show her bedazzlement on coming closer to the Museum of Man in Paris, in whose premises in the Palais de Chaillot, on the Trocadero, operated the Society of Americanists: copies of the Society’s Journal are in her library books that have reached us.

The Museum of Man was founded in 1938 by Paul Rivet who, at the time, had disturbed the scientific world with his theories – which later research was to confirm – with respect to the population of America, by claiming it was not formed just by entrance through the strait of Bering, but that it had taken place in different waves, in particular from southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands.

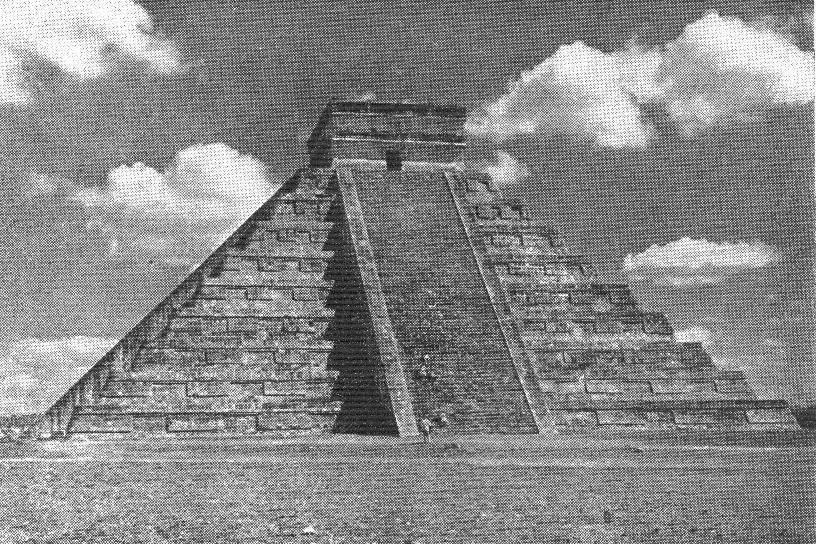

By the mid-20th century, the works of Laurette Séjourné could no longer be ignored and the Museum of Man had been converted into what could have been called “a center for discussion of American themes”, where, among others, the presence of André Metraux, the great Swiss ethnographer who worked in our forests, was a constant. These researchers, in spite of working in different geographies, converged with respect to the philosophical aspect of the American world. However, it was Mexican art that Drew attention in European

circles. Since the conquest, México had always had excellent chroniclers, in addition to precious codices and, in so far as the great Mayan culture, the knowledge grew with the capacity to decipher its written form. This entire body of information was maintained in great museums, both in Europe and in the United States, and in our Latin American institutions and there was a need to up-date in connection with this knowledge.

Magda Frank became impregnated with this knowledge in Paris, not only about western art but also about cultures that, decades before, had been the new source of interest of great painters and sculptors, among which Picasso, who enriched art with a new look on the archaic, Mediterranean and African art worlds. African art had a decisive influence on cubists for trying to be not just an aesthetic expression, but also striving to be efficient in relation to the world of the gods, of the mythical.

Magda’s first encounter with artistic manifestations of the American continent occurred in Paris, in her contact with the art of Mexico.

Ancient Mexican art is rooted in what is seen through myth. Hummingbirds are not just mere birds with iridescent feathers, but under its apparent forms, it is what the myth makes of it. From there, it converts into a symbol of rebirth, regardless of how much agreement there is with the natural model.

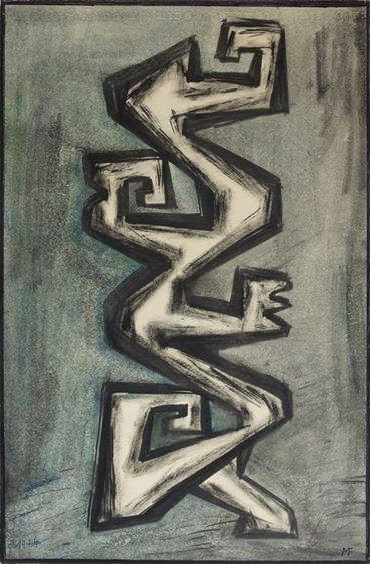

On the American continent, archaic art has been studied and observed from different points of view. The first one possibly being a conservative stance, a fact that has been repeatedly signaled. The persistence of drawings of a symbolic nature has been with us for millennia. Abi Warbourg, European art researcher of the late 19th century, could not help but be surprised by the continuity of the pre-historic drawings when visiting an Indian people in North America do Norte. Illustrations: two millennial drawings

Both the ancient spirals and broken straight lines – zigzag – coexisted in this people’s daily activities com drawings and objects corresponding to the moment in which Warbourg met them. These drawings of prehistoric origin are currently object of studies, since they were found in our Patagonia, as well as other places in America.

It is said that in Meso-American art there is an authentic artistic realism, since even if their reality takes a different direction from Hellenic realism, ancient Mexican art displays a striking mythical realism. This, and no other, was their reality.

Myth ruled their lives and influenced every aspect of daily life. For man in these archaic societies, myth is a reality that shapes and informs life, their way of thinking, their awareness and their subconscious. Thanks to myths, man understood the cosmos and their position within it; through rituals, even when these were very cruel, they preserved cosmic ordering. We must bear in mind that mothers cried when their young sons went off to war; the young man adorned as a god was offering, with his heart, the possibility of bringing the benefits of rain to his community. From this darkness, the cycle that brought light would be renewed.

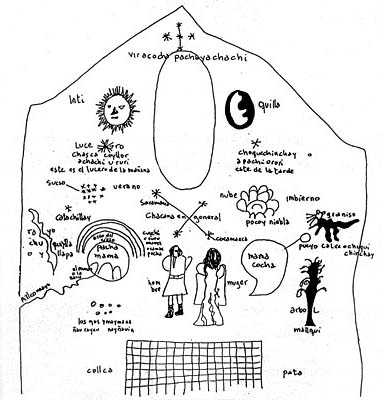

The major cultures of the continent displayed striking similarities. In these pre-Hispanic cultures in South Ameirca, in especial in their beginning, in the period known as Formative or Archaic, the world was represented in its horizontality by a four-way division and in its verticality, in three planes, on which our material and spiritual lives would take place. These planes have the following names in the Andean world: Uku Pacha, the inferior plane, corresponding to our ancestors and to those as yet unborn; Kai Pacha, the world of the living and, finally, Hanan Pacha, corresponding to the world above. In our ancient American cultures, and this is seen clearly in what was garnered from Mexican (Mayan) thinking, for whom life on Earth is perishable, but life energy is indestructible. Therefore, it cannot end or disappear. Bodies are just appearance which is then transformed in eternal, leading man to be but a part of a path. That is what can be understood in the Náhuatl:

“We came only to sleep

We came only to dream,

It is not true, it is not true

That we came to live on Earth.”1 (1)

Bernardino de Sahagún, Franciscan friar who left us a wonderful chronicle of Mexico, in which he explained that the ancients used to say that in dying men did not perish, but rather started to live again, transforming into spirits or gods.

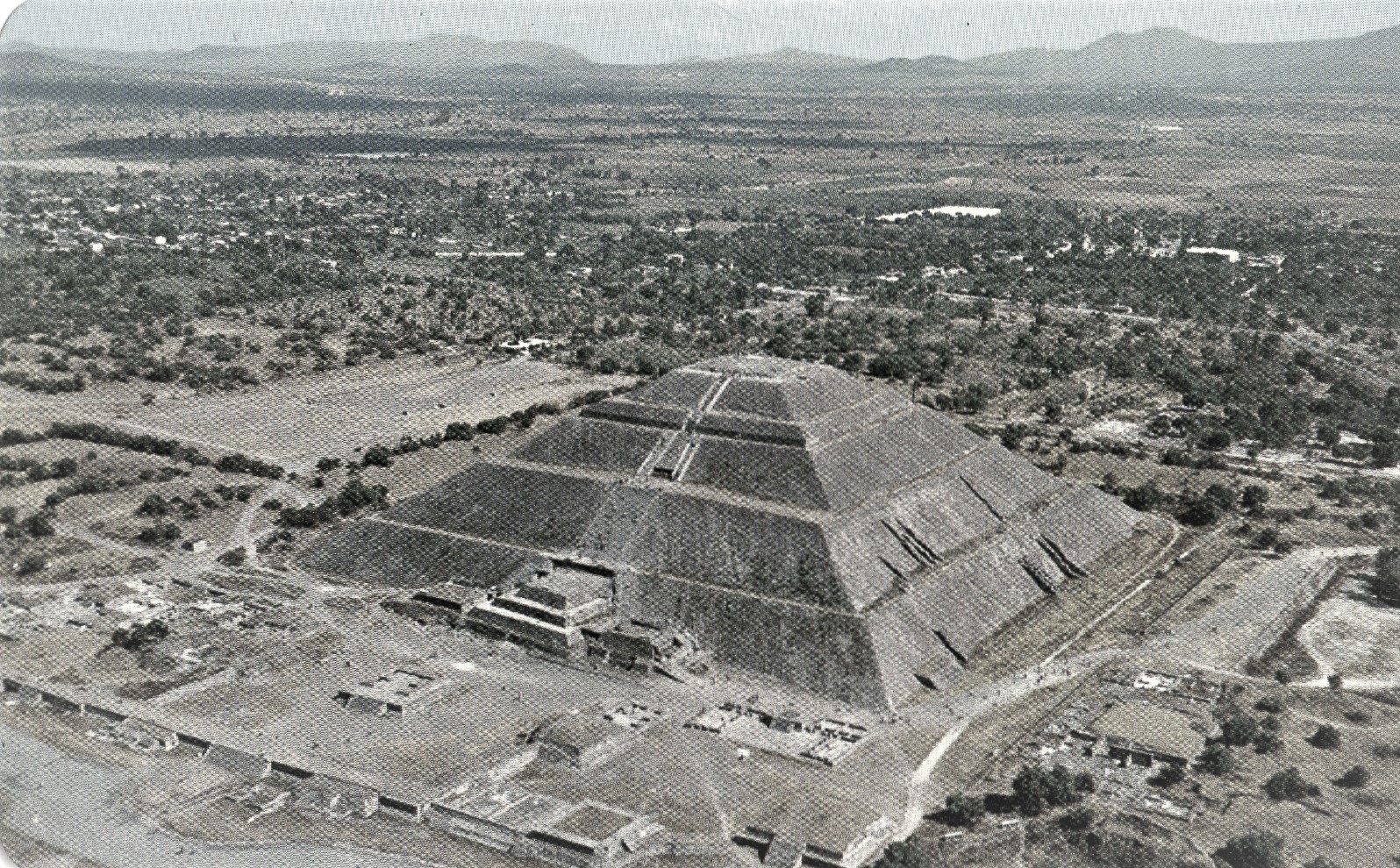

We believe our artist, Magda Frank, basically centered around the art of Teotihuacán. We are aware of the existence of different styles within the large areas of the central American nuclear cultures. Mexican Alfonso Caso distinguishes the “realism of Aztec art”, from the “impressionista realism of Tarasco”, or the “abstractionist Toltec art” and the spiritualized art of Teotihuacán, whose more bloody aspects occur when under a strong “theocracy”. But Teotihuacán is considered the center of this universe of beliefs.

Observing duality

We must bear in mind that for Séjourné, the metropo lis of the gods, as Teotihuacán is called, was nothing less than the place where the serpent miraculously learned to fly, that is, where individuals reach the category of being celestial, by inner elevation.

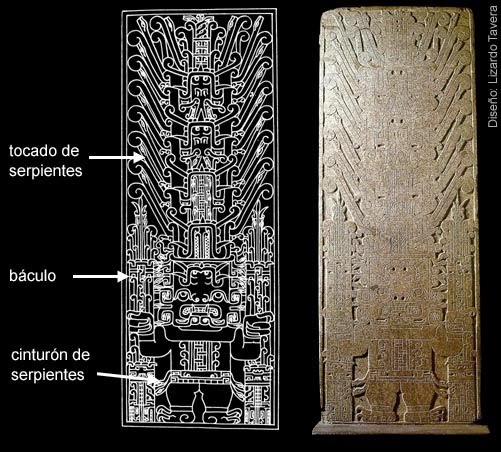

Laurette Séjourné also does mentions something that archeology had already proven, the fact that stylized serpents were common through out the American continent2. Whether in a step frieze, as S-shaped motif, or interwoven reptile bodies, they all capture the representation of movement. The serpent is always attributed a function of generation and, in terms of what makes its realistic figuration real, in the erect position it illustrates thinking underlying certain Náhuatl poems on human verticality. Literally, Quetzalcoatl means bird with serpent resources, for while the reptile tends to gain the skies, the Bird aspire to reach the ground, which seems to be indicative that the movement is conceived as ascent and descent, light and shadow. Quetzalcoatl’s message consist in solving the problem of duality in human nature.

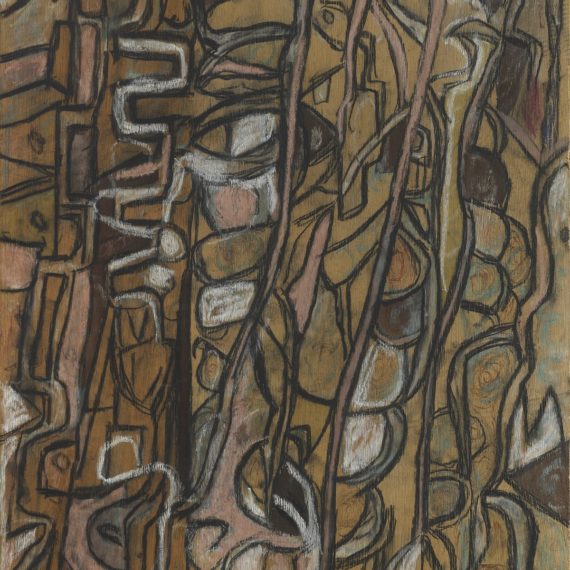

Magda Frank’s Works reveal how moved she was by the plastic expressions that refer to this duality. The duality of the American world is present in both Central America and in the Andes. This is certainly what led her to state that “pre-Colombian ar tis close to contemporary abstract and surrealist art, because they are pure creation, stemming from human phantasy and not from imitation of objects found in the external world, like in classical European art, one more reason for us to come closer to the art of this ancient land”.

For Germain Bazin, the theme of human unity – duality is persistent in art and its best manifestations occur in pre-history3. In addition, this author removes straight and curved from those days, associating them to musical expressions and linking curved to melodic and straight to rhythmic. This sign leads us to the confirmation that they were living in mythical times, a sacred time in which all we call art was unified.

Most of Magda Frank’s sculptures allude to dualism. So, if take one

of her works as reference, Ritmo octogonal (Octoginal Rhythm) – sculpture on wood from 1964 – we will glimpse not only the search for a personal and contemporary plastic language, but also the echo of ancestral rhythms. Her work remits to the deepest there is in the symbology of the pre-Colombian universe. Verticality is a predominant profile and, if we go back to what Séjourné said, we are faced with an essentially human resource highlighted in the legacy of Teotihuacán. The figures of hooks, omnipresent in the step pyramid, are also present in the work of Frank, in the same form that they are found in pre-Colombian culture throughout America. Based on this we should bear in mind archeologist of the Andean world, John Rowe, when he said that a simple hook or claw with hold a strong power of evoking on anyone who saw it, because the observer knew the story, once the drawing would be associated to oral tradition. The synthesis of the idea is present in part of the whole; this principle, also established for Andean tradition and associated to the entire American universe is unequivocal in the work of Magda Frank.

THE CULT TO ASCENT

In the Andes, colorful birds did not just populate many of their spaces, according to Cieza de León’s narration in his chronicle, they also went along with Huayna Capac and Tupac Inka Yupanqui on his journey along the entire coast. In spite of each culture establishing its own aesthetics codes, the symbolism of the feather ornaments is even broader, because adorning their bodies confers on individuals the status of man, differentiating them from the other living beings that live in the jungle and also distinguishes them from the other Indian groups. Manufacturing these objects implies for those making an aesthetic intentionality and a deep knowledge of the symbolic meaning of each plume, each color, each part of the adornment to be worn exclusively on specific occasions (4).

6 Tumi o cuchillo Vicus. 100 a.C. a 400 d.C.

For some reason we do not know, Magda Frank also toasts us with a report very similar to a myth of creation, where birds have striking roles. She tells it like this: “A long time ago… when Paradise was on Earth, and men lived in other planets, trees could walk, like you or me. They were the dear offspring of the Sun and the Earth. In the morning, after turning their smile to the Sun, they came down to the river in long lines. Birds of all colors kept them company along the way. When the Sun hid, the trees spread out over the plain, hosting birds to allow them to dream. One spring day, when flowers were blooming, the trees got together in a huge field and, taking advantage of a passing breeze, took a low leap, distancing from the Earth. The Earth accepted the game and placed them on a cloud, where they stoneed themselves to sleep, like the angels in our dreams. But, suddenly, the glacial wind, enemy of the Sun and of the Earth, arrived coming from far away. Without any doubt, it made the trees suffer with its with its ravening teeth and beams of fire, breaking their branches and flowers. The lifeless trunks fell onto the Earth, which opened up its bosom to save in it the little there was left. The Sun hid its face so they would not see its tears. The birds bowed their heads in the dust, their desperate lament echoing throughout the desert world. The Sun, moved by so much sadness, caressed the Earth with its eternal heat, and the trees were born again from their mother, who never again allowed them to move away from her”.

The symbolism of the art of plumes is, for us today, largely alien and, therefore, a merely aesthetic fact. For this reason ethnographers, like André Metraux, affirm that myth is for primitive man the expression of their mystical representations, the concrete product of their own mindset. In order to be able to understand them, in sense and meaning, we would need to think in a way analogous to them and abstract ourselves from all our intellectual habits 5. In this same sense, Magda Frank stated that: “If from every work of plastic art, the story and philosophy they tell are removed, what is left for observation is nothing but a decorative object. A creation in plastic arts that must enclose in itself its time and history, transmitted through its shapes, its colors, its rhythms, for visual elements and not by written or spoken words. Through anyone who, by looking carefully, captures the artist’s message”.

This thinking by Magda Frank coincides with certain expressions by André Malraux, when he claims that the value of modern art reaches us, not by representation, but by poetry, by music and by romances, born out of the atemporal. “Because the atemporal is our own precarious eternal rebirth”6. Malraux explains in this way the way cubist artists joined African art and archaic art in general, in forms of manifestation found beyond chronology. The 20th century was a century of searches, ancient fears in connection with the fate of man and, in a few artists, an intimate rebellion made evident in the desire to find their origins again, as expressed by Gauguin.

It was precisely Gauguin who initiated the presence of America in European art, since up to that point in time, only what happened in the continent was taken into account. Gauguin, perhaps for being a grandchild of Flora Tristán7 and having lived with his mother in Peru until he was nine, depicted himself in ceramics in a way that was analog to the portrait-vases of the Mochicas8. This so called “new primitivism” influenced many artists, who were documented in museums or private collections. There is no doubt that pre-Colombian art appeared to them as hieratic and monumental, and for this reason was more influential in sculpture. In the 1940s, Nazism considered primitive sculptures, as well as all world inspired by it, to be enemies of their system. One strong example of this is the totalitarian regime’s repulsion for Picasso’s work. Without any doubt, for Magda Frank, this art was a form of protest. Perhaps it was for this that, in referring to her sculptures, she said ”(they) must accuse, shake up human conscience, brake the desire for destruction that, in some people, is the strongest feeling”.

The search for the innocence of the original state seems to always have been present in Magda Frank. Her constant evocation of childhood, of tales, of dolls, the pleasure she feels in working with clay, one of the first materials with which man started his creative activity, everything seems to led her to pre-Colombian art. Magda Frank confessed: “Deep down, I’m from Transylvania, and as a child I saw them sculpt small figurines using penknives. Each after noon I pick up the items in wood, I polish them and give them colors with paint. They multiply, I call them ‘my dolls’”. Childhood and games are directly associated to the

desire of recovering the original innocence, of times past, without the clouds of evil. Pre-Colombian cultures, with their cyclical concept of time and the idea of the search for an even higher plane, that is, the last stage in Hanan Pacha”, offer the possibility of bringing them closer, going towards the desired meeting with dawn.

The idea of dawn is not associated just with sunlight, but also with birdsong. The marked presence of wings in Frank’s works manifests itself even before her approximation of the pre-Colombian world, this symbol of spirituality will be a constant presence in her work. In the American world, the serpent bird mentioned by Séjourné is not alto gether distant from a universe of representations.

The rich feather headdresses that awe Durero in 1520, making him say “that, in all his life, he’d never seen anything that so much joy brought to his heart”, are also found in the peoples of the Amazon. Both Paul Rivet and Lévi-Strauss anticipated some of the theories that we are currently reviewing and that support the existence of ancient connections among the different pre- Colombian cultures.Art in feathers, in its different manifestations, appears throughout the continent and this is no coincidence. It is inextricably linked to the attraction of men for birds and their aspiration to reach the sky, of raising themselves out of materiality. It underpins the entire civilization present in Magda Frank when she says that “tradition is formed by tiny links on a long chain: human civilization. Sculpture is, quite probably, the oldest unchangeable expression of mankind”.

THE BANALITY OF EVIL

It would not be too much to think that Magda Frank finds in pre-Colombian art a possible alternative to the horror of the Holocaust. Having lost her entire family, this experience remains marked by the definitive absence of her brother Bela, whom she evokes in her texts and to

whom she would like to give new life in her works. As well as supporting Burucúa, because in antiquity mass annihilation was used as form of legitimating the power do sovereigns over their followers, as a strategy of domination. When referring to the massacre of the inhabitants of the island of Melos during the Peloponnesian Wars, Burucúa says “the facts are told by an Athenian who belongs to the party of the ones who perform the act and he finds himself having accepting it. He cannot feel they are right”9. Evil appears in a few moments of human society as a banal fact, bare of meaning.

According to this, it is evident that our artist faces the irrational, everything that crushes her, even hope itself. There is no doubt, she believes that has found in the archaic shapes a new dawn. Something that does not seem to be too distant from what Hannah Arendt manifested in saying: “Times of obscurity in their broadest sense that I hereby propose, are not equal to the monstrosities of

this century, which in fact constitute a terrible novelty. (…) Even in the times of the deepest dark we have the right to expect a certain light, and that this light may come less from theories and concepts than from the wavering light, shiny and at times weak, that some men and women will shed on their work, their lives in nearly any circumstance and on the time in which they were alive on Earth (…) Eyes as used to darkness as ours can only distinguish between flickering candlelight and bright sunlight” (10).

“My older sculptures date back to the first years of the post-war. Having survived the catastrophe, I was invaded by a strong desire to enjoy life. This desire manifested in the drawings or sculptures of this time, representing wavy, sensuous female figures”. With these words, Magda Frank begins her reconciliation with life, in the profoundest sense of the term “religare”, reconciliation with others, with the world. If we think about Derrida and his reflections as to the implications of “religare”, we think about his option for the return of the primitive and archaic11. In this sense, our own artist affirms: “In the last years, I did polychromatic works with a happy spirit, this might perhaps be my reconciliation with human tragedy”.

MAGDA IN THE SOUTH

Close to the mid-20th century, Magda arrives in Buenos Aires and in little time adopts Argentinian citizenship. Among her memories, we can find a few catalogs and drawings that

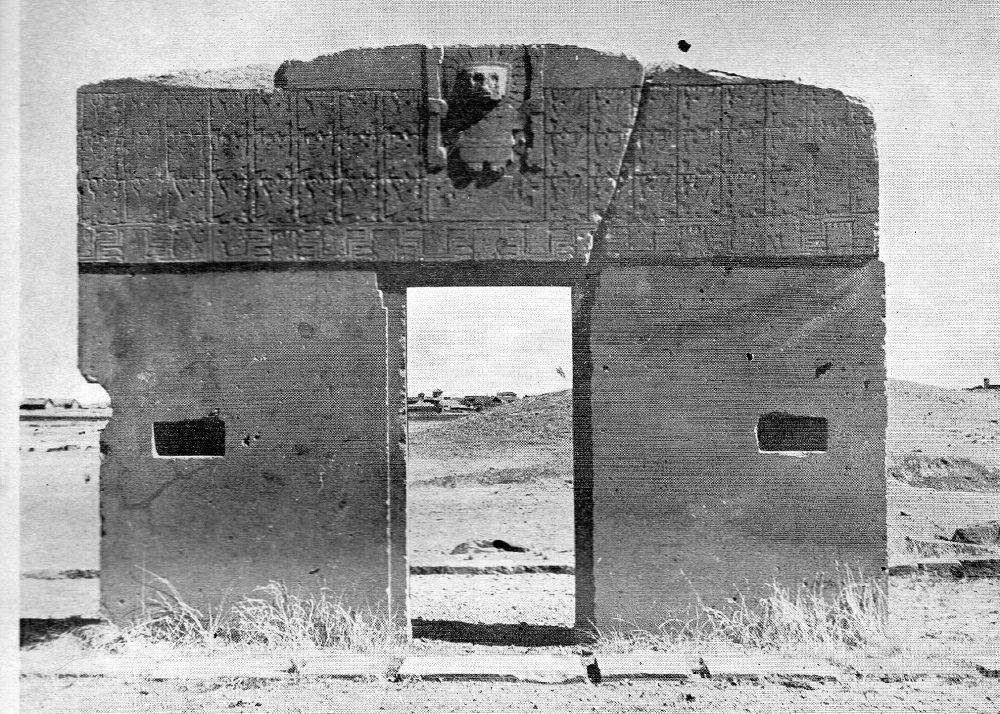

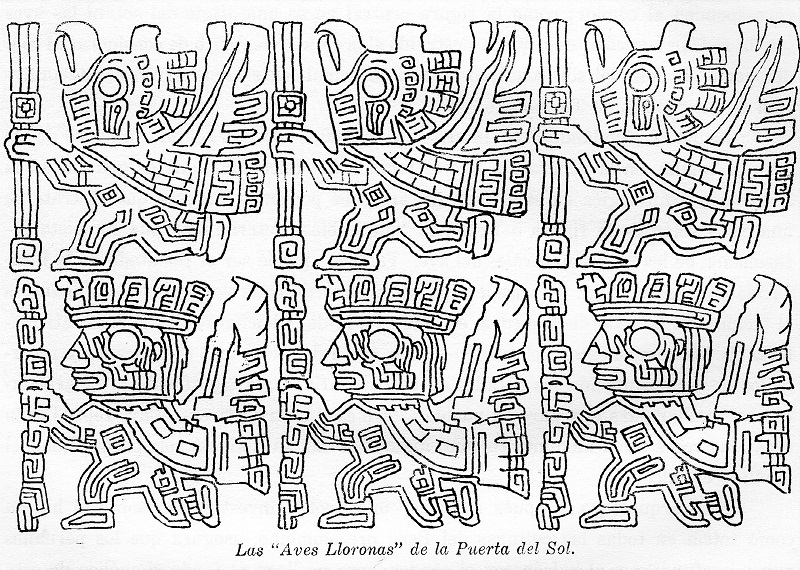

denote her visits to the Juan B. Ambrosetti Ethnographic Museum, at the University of Buenos Aires. There is no doubt that, in spite of not having been able to travel to the Andean world, as she desired, her work is influenced by this new environment. In this museum , the two trails that might have awoken her idea of bird as a spiritual theme have always been present – the trail of Chavin in Peru and the figures of the Sun Doors in Tiahuanaco.

Both trails, separated by centuries, allude to the theme of man – feline – bird and, obvious, spiritual ascent. This artist possibly found here what she had glimpsed in Mexico.

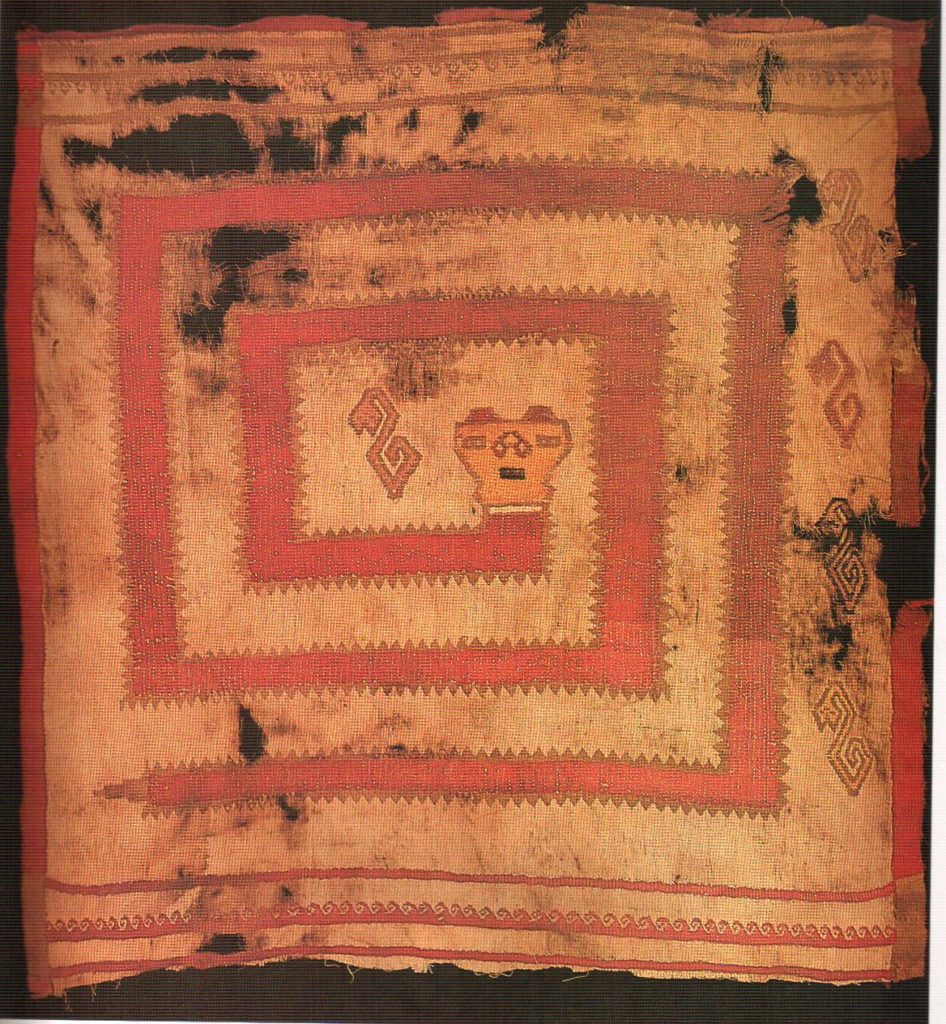

Anthropologist Frank Boas was one of those who signaled with the utmost clarity the characteristics of these ancient expressions within the art of the Andean world. With respect to the fabric, Boas expressed that the rhythm of American textiles was based on reiteration and symmetrical alternation. Then he showed how monotony was avoided by rotating motifs and colors. Other researchers signal that in other archaic cultures, reiteration was as part of a rhythm tied to holy life, i.e., to prayer.

It was in the studies done in Argentina, that Magda Frank probably learned when she visited the Ethnographic Museum, of the research done by Juan B. Ambrosetti, Debenedetti and, in the mid-20th century, by Dr. José Imbelloni.

Cerámica del Nor Oeste Argentino,

Colección Ministerio de relaciones exteriores y culto

Cerámica del Nor Oeste Argentino,

Colección Ministerio de relaciones exteriores y culto

Cerámica del Nor Oeste Argentino,

Colección Ministerio de relaciones exteriores y culto

Previous

Next

In the years of the 1950s, the presence of Amazonian material took new strength and vigor. The work of ethnographers Enrique Palave cino and his wife Delia Millán focused on the zone of the Chaco. The forest was not too distant12.

The Ethnographic Museum already had several collections of objects in feathers from the Amazon, in particular from the Chamacocos, tribal group geographically located between Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina.

Museo Etnografico Buenos Aires.

Tocado de flamenco. Grupo Wichi. Foto de E. Palavecino. Orán, Salta. 1938.

Museo Etnogtafico, Buenos Aires

Silbato Amazonico.

Museo Etnogtafico, Buenos Aires

Tocado chamacoco amazonia

Previous

Next

One of the issues that most drew the attention of anthropologists and ethnographers recently is the relationship and persistence between the vision of the cosmos of Amazonian peoples and Ara. The association of Guacamayo and rising to the skies was found among the Bororó of Mato Grosso. As pointed out by Ruben Reina in The Gift of Birds, the cult of birds has in this cult culture of the Bororós its most vivid representation. The work of researcher Elizabeth Netto Calil Zarur leads us to know the ideal floor plan for a Bororó village. It coincides with the ancient American theme of the division of the world into four parts and the duality of man. In Bororó villages, the various groups are associated based on the colors of the plumage of birds. Red is connected to the sun, fertility and women, while black is associated with men, ancestors, the darkness and the night:

…..“The Bororó believe that all physical things have ‘soul’, called ‘aroe’, etymologically derived from the word ‘aro’, meaning feather or something as light as a feather (ghost or spirit), this word is also used to describe a small and fin plumage. The Bororó explain the meaning of ‘aroe’ as soul, the Portuguese word for ‘spirit’ in the Christian concept”13.

For the Bororó, “Aroe” is the immortal spirit of all things and living beings. The ancestors and heroes of the Bororó culture, who live in the “village of the dead” are “Aroe”14. When a Bororó died, he was wrapped in leopard skin and among his last possessions, was the infallible crown of feathers, allusive to the “Aroe”.

We know that in ancient Peruvian cultures, feathers played a predominant role in the sumptuousness of the rites. On the north coast, Moches and Chimúes developed a scenario in which plumage represented power. Like Mexico, the lords or Curacas had to identify themselves with the power of intercession between the material and the Hanan Pacha. The Inca state, whose origin was in the Amazon region, used these same symbols. The painting of the Viceroyalty of the late eighteenth century shows us some Curacas with their headdresses. These groups included llautu (fore head band) mascapaycha (edge) and coriquenque (set of feathers of a sacred bird), summarizing their vision of the cosmos.

We know that in the Inca state, as in Mexico, there were many experts in the art with feathers. Currently, in the Amazon villages, we still find evidences of this and we can glimpse this magical moment of creation of a feather ornament in a report by Ticio Escobar:

“It’s the white and vertical siesta of the Chaco (…) Squatting, the Indian did not break the spell that paralyzes the palm grove and the village, his calloused hands move only around a small net extended with a carob stick. (…) With a very fast gesture, he suddenly stretches his hand to a parrot pelt, with all its feathers still in place, stuck close to his feet in a cross stake. He draws a handful of green feathers and starts placing them, piece by piece (…) He finishes the green row and begins a yellow one (…). Like a magician, he has a handful of black Chupim feathers appear in his left hand” (15)

This practice acquires mythological aspects of the jungle when it comes to macaw feathers, name used by the Guacamayo people to define themselves. These feathers are present in their mythological tales of their own origin, in which the ancient dispute between sky and water is re-enacted, and the guacamayos take some men to the sky and become stars, while others remain trapped in the jungle. Today we find ourselves trying to cover the sacred paths.

THE SACRED PATHS

Today’s advances in archeology and ethnography allow us to follow the sacred paths. For millennia, the three geographic regions of South America: coastal, mountain and forest were connected. The central southern Andes has been linked by llama caravans (llameros), which was corroborated by the common elements found along the Atlantic coastline, in offerings in the high mountains and on the Pacific coast.

The main theme of the art of northwest Argentina is the symbiosis between the figures of the shaman and the jaguar, in spite of there being some other themes such as snakes, llamas, birds and bats. In societies such as the Andean ones, where the sense of the sacred is so central and fundamental, that earthly power does not depend only on the strength and capacity to impose on others, but also the wisdom to articulate the relationship between heaven and earth, and sustain this balance in benefit of the community. For this reason, in the Andes, power and religion are two very close conditions. (16)

Estatuilla de Loro Huasi, cumbres andinas. Direccion de Antropología bProvincia de Catamarca, Argentina

Until the mid-1950s, Magda’s drawings show us the importance the subject of angels had for her, an old theme that she does not disdain

the post-conquest period. Demonstrating this is the remarkable map of “El Paraíso” by Leon Pinelo (1596-1660). In his book, El Paraíso en el

Nuevo Mundo, he places the Eden in the Amazon jungle between Peru, Bolivia and Brazil (16).

The Guarani peoples – as we have seen – had as end point for their mythology this celestial world: the Land without Evil. The South American continent would be the site of the Eden, a Paradise-like place for men who for centuries

had believed in it.

t was not only the myth of material wealth that fueled the legend of Paititi, for some men it was the possibility of recovering a deep reconciliation and, with it, the lost or hidden wisdom. It may persist as the old projects that have lasted millennia and that haunted Warburg.